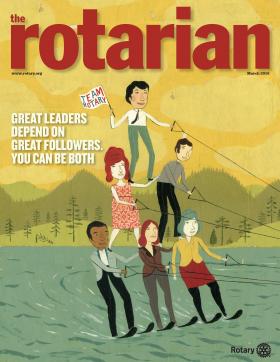

Best in a supporting role

From the March 2016 issue of The Rotarian

I believe I am safe in assuming that most of you are not regular readers of the Journal of Leadership Studies. Nor that you had the pleasure of perusing the article in that magazine’s Winter 2014 issue titled “Followership in Leadership Studies: A Case of Leader-Follower Trade Approach.” To save you the trouble, let me summarize the argument put forward by the author, Petros G. Malakyan:

While an abundance of research is devoted to leaders – an entire literature, in fact –almost nothing is written about followers.

The reason for this is not particularly elusive. From presidents to mob bosses, from generals to drug lords, we love narratives that center on figures who hold, or aspire to hold, absolute power.

Illustration by Bjorn Rune Lie

This bias is even more pronounced in the world of business, which is predicated on the notion that worth can be measured by your place in the pecking order. People don’t think about how they function as followers because the very idea that they might be followers – as opposed to leaders-in-waiting – strikes them as insulting.

The huge and unsung irony here is that most leadership studies conclude that lousy followers wind up making lousy leaders. “He who has never learned to obey cannot be a good commander,” is how Aristotle put it a couple of thousand years ago.

This dynamic is particularly fraught for Rotarians, because Rotary is, by its nature, filled with people who are leaders in their profession or their business who must adapt, or re-adapt, to being followers in order to function within the organization. For this reason, I’ve spent several weeks studying the concept of followership and trying to compile a few crucial tips to being a good follower.

It’s certainly fair to ask what my qualifications are for this task, so let me set out my bona fides as a follower. Ahem. Aside from editing my college newspaper, I’ve never actually been a leader of anything – and that includes my family, a small, volatile start-up operation that is indisputably helmed by my wife.

What’s more, I make my living mostly as a freelance writer. To remain employed, I have to be not only a good follower, but a good follower to about two dozen leaders, each of whom has a different style. The only thing they appear to have in common is a tendency to ignore my emails.

***

There are four essential qualities to being a good follower, at least according to Robert Kelley, a scholar at Carnegie Mellon University who enjoys the odd distinction of being the world’s leading authority on followership.

A couple of these are pretty straightforward. Good followers have to be committed to the mission of the group, and they have to be competent in their given role. The more nuanced attributes are what Kelley refers to as self-management and courage. Good followers have to be able to work independently and maintain their ethical standards.

The most common misconception Kelley encounters is that being a “good follower” is tantamount to passive obedience. In fact, a good follower must be engaged in an active collaboration with the leader, and that requires critical thinking. Followers must be candid with superiors, especially in offering constructive criticism that might aid the larger cause. In the absence of critical thought, groupthink inevitably takes hold.

What’s most fun about reading Kelley’s work is the spot-on taxonomy he provides of follower types. Anyone who works in an office will recognize them.

The “sheep,” for example, require constant supervision. The “yes people” put blind loyalty before all else. Then there are the “pragmatics,” who wait until a consensus has emerged before taking a position on anything. And, of course, the “alienated,” who are motivated mostly by grievance, the not-very-secret sentiment that they are the ones who should be in charge.

My sense is that most followers struggle with all of these tendencies. They are natural responses to the dilemma of the follower, which is that you are expected to devote yourself entirely to a cause that brings more glory (and riches and a bigger office) to the leader, not to you.

This expectation may be especially difficult for Americans to accept because it runs up against a basic tenet of our culture: exceptionalism. As a political system, of course, capitalism has been wildly successful in motivating people to strive for greatness. But it also defines greatness in narrow terms. To put it bluntly, you are the top dog or a nobody.

But the hallmark of what Kelley calls the effective follower is precisely this: an ability to check your ego at the door, to remain positive and self-motivated even if you’re not setting the agenda. This person succeeds even without the presence of a leader precisely because she embodies the ideals of leadership.

Kelley’s point is ultimately the same as Aristotle’s: The key lessons of leadership are learned as a follower.

***

As a resident of New England for going on two decades, I’ve been a witness to one of the most striking exemplars of this maxim. His name is Tom Brady. The quarterback of the New England Patriots is widely regarded as one of the best players in history and the league’s most natural leader: gifted, smart, hardworking, and able to inspire the best in his teammates.

But fans tend to forget how the Brady saga began. When he came to the University of Michigan, Tom Terrific was a tall, gawky kid from a private California high school. He was listed as seventh on the depth chart and spent his first two years as a backup.

Despite two outstanding seasons in college, Brady wasn’t considered athletic enough to make the pros. He was lucky to get drafted late in the sixth round. He arrived in training camp with three quarterbacks ahead of him, including a star named Drew Bledsoe.

Once again, Brady accepted his role as a follower. He never complained to coaches or allowed bitterness to infect his work ethic. He carried Bledsoe’s clipboard and remained eager to learn from him.

Early in his second season as a pro, Brady was called upon to replace Bledsoe, who had been injured during a game. Within a few weeks, it was clear that Brady would hold the job for the rest of his career. But the seeds of his success as a leader were planted during those months and years of toil as a backup, when Brady made the largely invisible decision to embrace the role of a follower.

This is not to say that Brady has always adhered to the highest ethical standards – the “Deflategate” saga clearly raised questions about his willingness to win at all costs. But most of those criticisms have come from outside the sport. His teammates have supported him unconditionally.

You can trace the same pattern in the lives of figures such as Joshua (who faithfully served Moses and led the Jews into the Promised Land), Winston Churchill (who remained loyal to his predecessor Neville Chamberlain but questioned his appeasement of Hitler), and even Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. They all succeeded as leaders only after having to learn the lessons of good followership.

***

I fibbed a bit when I said I have no experience as a leader. As a teacher, I’m technically a leader whenever I step in front of a class. But any success I’ve had as a teacher arises directly from my experiences as a student.

This started years ago, when I took my first writing workshop. Our leader was a novelist named John Dufresne, one of my literary heroes. I expected, and hoped, that the class would consist of Dufresne holding forth to his acolytes.

Instead, he pushed us acolytes to take the lead, serving more as a guide and swooping in to steer the conversation only when we veered off course. It was from him that I learned the essential goal of teaching, which isn’t to show students how brilliant you are, but to inspire their own brilliance.

A class succeeds not because the leader has all the answers (thank God), but because followers come to recognize the value of developing their own critical faculties. Without exception, the students who learn how to critique with both ruthless and tender precision are the ones who wind up publishing books down the line. I’ve seen this pattern play out over and over in my own workshops.

So far as I can determine, being a good follower boils down to acceptance. You have to be OK with the idea that you can achieve simply by contributing.

To offer your full devotion as a follower isn’t an act of acquiescence or resignation. On the contrary, it’s evidence of a healthy ego, of a person bright enough not to need a constant spotlight.

The question for all of us is whether we can find the grace required to be a follower in good faith – to accept that cooperation is not the enemy of ambition and that recognition never brings us enduring happiness unless it comes from within.

The Rotarian